Health and Environment and the 2030 Agenda Every minute, five children die from malaria or diarrhea; every hour, 100 children die from indoor smoke exposure to solid fuels; every day, 1,800 people in developing cities die due to urban air pollution; and every month, nearly 19,000 people in developing countries die from unintentional poisonings (1). The world is living dangerously – either because it has little choice, which is often the case among the poor, or because of limited regulation (imposed by citizens, corporations or governments) on environmentally damaging activities.

World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 24% of the global disease burden (healthy life years lost) and 23% of all deaths (premature mortality) are attributable to environmental risk factors, with the environmental burden of diseases 15 times higher in developing countries than in developed countries. The World Bank estimates that air pollution alone is costing India approximately 8.5% (560 billion USD) of its GDP every year (2).

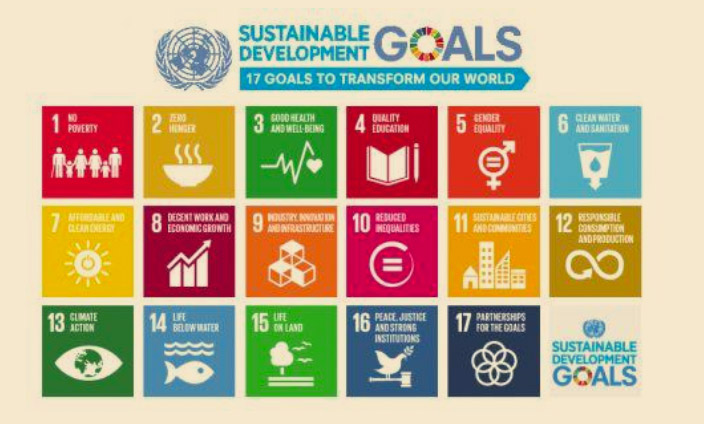

Source: United Nations

The global community has developed an agenda that promises to address the concerns of human development while ensuring the health of the planet and its ecosystems. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) embrace the need for economic development in a more holistic manner than was done previously under the Millennium Development Goals. The most common definition of Sustainable Development from the Brundtland Report defines it as “Development that meets the needs of present generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own.” Therefore, the SDGs with its 17 goals and 169 targets integrate the broader health issues within the social, economic, and environmental aspects of development. According to Professor Srinath Reddy, President of the Public Health Foundation of India, “the strength and the challenge of SDGs lies in their interconnected agenda of

interdependent goals.”

Some of the critical targets unanimously agreed upon in the SDGs include efforts to address the environmental health burden of disease. Goal 3 addresses all major health priorities, with target 3.9 seeking to substantially reduce deaths/illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination. Goal 6 addresses the issues relating to drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, together with the quality and sustainability of water resources. Goal 11 supports monitoring of environment/health dimensions through its emphasis on making cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable. Goal 13 recognizes that climate change presents the single biggest threat to development, and its widespread, unprecedented impacts disproportionately burden the poorest and most vulnerable.

In 2016, India ranked 141th out of 180 countries on the Environmental Performance Index (EPI), moving up from its rank of 155 in 2015. EPI is an index which measures national and global protection of ecosystems and human health from environmental harm. The climb up the EPI ladder can be attributed to several efforts undertaken by the government. With air pollution becoming the major contributor to the national disease burden (Global Burden of Disease Report, 2015), the Ministry of Environment and Forests and the Central Pollution Control Board launched the ‘Air Quality Index (AQI)’ tool in April 2015 to monitor and regulate air pollution. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Steering Committee Report on Air Pollution notes that 1.04 million premature deaths and 31.4 million DALYs are attributed to household air pollution resulting from solid cooking fuel use in India. The Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana launched in 2016 to provide LPG connections to 50 million women living below the poverty line will help reduce the burden of household air pollution related morbidity and mortality. According to Swachhta status report 2015, 52.1% of the country defecates in the open. The Swachh Bharat Abhiyan aspires to make India open defecation free by 2019.

Clean energy, environmental protection, biodiversity, and urban design will all need to be accounted for if India is to meet its development targets in a sustainable way while ensuring its population’s basic needs of access to clean air and water, education, and healthcare are met. India has signed the Paris Climate Agreement, the first-ever universal, legally binding global climate deal to cut greenhouse gas emissions, and to limit average temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2030. Other corrective measures could include allocating a percentage of the budget to the environment and to build in environmental objectives into taxation policies, procedures for investment and technology choice by awarding incentives. Concerted and immediate efforts to provide safe drinking water, useable toilets, and clean cooking fuels; address the growing solid waste management needs; provide clean energy solutions with solar energy expansion and provision of non-polluting fuel for motor vehicles are the need of the hour.

National governments, alone, cannot realise these ambitious goals on their own. Collective and individual efforts at the local and national levels are critical. There is need for a broader involvement of stakeholders including the private sector, the general public and civil society organisations. Several World Bank-supported projects have shown that communities can respond to their own development needs, at lesser capital costs with facilitation by local governments. With the help of the Jharkhand Government and local volunteers, the NGO Action for Community Empowerment helped make Gadri the first Open Defecation Free village in Jharkhand. In 2015, Uttarakhand inhabitants built their own water supply systems, benefitting 1.5 million rural residents. The Jalanidhi project has helped provide dependable supply of piped water, as well as water storage facility to 192,000 rural homes in 13 districts of Kerala, at highly affordable prices. With support from the Indian Oil Corporation, Vyachakurahalli village in Karnataka became India’s first smokeless village with 274 households switching to LPG from biofuels. Community-led efforts have put Mawlynlong village in Meghalaya on the world map as Asia’s cleanest village. A strong political-will combined with public-private partnerships will be needed to meet India’s SDG targets.

“There can be no Plan B, because there is no Planet B, the future we want lies in our hands”

— United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon

Research Spotlight

Cardiovascular Benefits of Wearing Particulate-Filtering Respirators

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated a consistent increased risk for cardiovascular events in relation to both short- and long-term exposure to ambient particulate matter. The Global Burden of Disease Report (2015) lists air pollution as the number one risk factor for death and disease combined for India. The report also lists heart disease as the number one cause of death

and disease in the country.

Environmental health policy interventions have a substantial impact on the health of populations as has been seen in US and Europe. However, such environmental interventions take time to implement. Therefore, more practical solutions to reduce individual exposure and protect public from ambient air pollution are required in the interim.

Source: Mail Online India

Air purifiers and particulate filtering respirators are some measures to reduce exposure to air pollutants. Previous studies have reported the health benefits associated with the use of indoor air purifiers. In a recent study published in Environmental Health Perspectives, researchers in China reported the health benefits of a simple face mask intervention.

Healthy college students with no history to smoking, alcohol use, and no clinically diagnosed chronic cardiopulmonary diseases were recruited for a randomized crossover trial. The participants were equally randomized into two groups and one group wore particulate-filtering respirators for 48 hr while the other group was the control (no respirators). After a 3-week washout interval, the groups switched with the control group now wearing masks for 48 hours. The intervention group was required to wear their masks all the time they were outdoors and as much as possible when they were indoors. The respirators used in the study met the N95 standards. Clinical parameters measured included heart rate variability and blood pressure, which were monitored during the 2nd 24 hours in each intervention. At the end of each intervention, circulating biomarkers were also measured.

During the intervention, the mean daily average of indoor and outdoor PM2.5 was three times the WHO guideline for daily average (25 μg/m3). Subjects who wore respirators had higher levels of most HRV parameters and lower levels of BP. Subjects wearing respirators recorded a decrease of 2.7 mmHg (95% CI: 0.1, 5.2 mmHg) in systolic BP compared with those not wearing respirators. Circulating biomarkers of inflammation, coagulation, and vasoconstriction were also lower in participants who wore respirators than those who didn’t.

Despite several limitations including a small sample size, short duration of intervention, and healthy subjects, the study provides preliminary evidence that short-term wearing of particulate- filtering respirators may produce cardiovascular benefits and lower BP levels. It also suggests that until such time that stringent health policies are put in place, respirators have the potential to offer protection from PM2.5 in locations with severe air pollution.

Researcher’s Perspective

Reporting from COP22

The twenty-second session of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) Conference of the Parties (COP 22), was held Marrakech, Morocco from 7-18 November 2016. Dr. Pradeep Guin of the Public Health Foundation of India, and Dr. Priya Dutta, Indian Institute of Public Health (Gandhinagar), and fellows at the Centre for Environmental Health, attended the 2nd week of the two-week long conference. They share their account of the various events at the conference as well as highlight important takeaways.

In 1994, the UNFCCC was created in order to combat adverse impacts due to climate change. Countries that have ratified the Convention are known as Parties to the Convention. Since 1995, representatives from these countries have been meeting annually in what is known as the Conference of Parties (COP), which is the “supreme decision-making body of the Convention.” The Marrakech meeting held tremendous importance, especially because it was coming after the adoption of the Paris Agreement (2015) and because it highlighted that countries were still trying to reach a common ground on operationalizing the Agreement. So far, 112 out of 197 Parties have ratified the Agreement which entered into force on November 4, 2016. The historic city of Marrakech provided the venue to the Parties for carrying out these negotiations as well as to propose new ones that are pertinent to providing a safe environment for current and future generations.

We were nominated by the UNFCCC Secretariat to be part of the delegation representing Health and Environment Alliance (HEAL) during the second week of the conference. HEAL is an alliance of around 75 organizations that focuses on providing information to various decision-making bodies involved in improving human health that is otherwise affected by changes in our environment. This year HEAL’s delegation to COP 22 comprised of members from India, Turkey, Belgium, France and Morocco. As young scholars, we were both excited and amazed to be part of this mega event. We witnessed how various stakeholders, including leaders from India and abroad, met, supported and negotiated for the cause to make the world a more livable place for the current and future generations through implementation of climate-friendly alternatives to benefit human health.

The HEAL delegation with WHO representatives and public health experts during a side event.

One of the highlights of the conference was the “Interministerial Meeting on Health, Environment and Climate Change” which was co-organized by the host nation’s Ministries of Environment and Health, World Health Organization and the UN Environment Programme. It culminated with the signing of the Declaration for Health, Environment and Climate Change by more than “two dozen Ministers and high-level officials from both the health and environment sectors.” Through global collaboration, this Declaration aimed at reducing the 12.6 million annual deaths due to environmental pollution, including over half of them attributable to air pollution. Another important event was the launch of the “Lancet Countdown: Tracking Progress on Health and Climate Change.” This countdown formally paved the way for an international, multi- disciplinary research collaboration among leading subject-specific experts to further advance our understanding on the impact of climate change on public health.

Mr. Anil Dave, Union Minister for Environment, Forest and Climate Change, addressed the participants about the importance of Gandhian lifestyle, which is sustainable and helps reduce our carbon footprint. On this occasion, he released a book on “Low Carbon Lifestyle – Right Choices for our Planet”. The Minister also stressed the importance of raising finance under Green Climate Fund (GCF) and the need for technology transfer. The Indian pavilion also hosted a panel discussion on the importance of solar power and demonstrated the national leadership’s commitment in promoting this sector through International Solar Alliance (ISA). A large screen LED display in the pavilion also highlighted several programmes such as Swatch Bharat Abhiyan, Ganga Action Plan, Diamond Quadrilateral project to establish high speed rail network in India, Beti Bachao Beti Padhao Andolan, etc.

There were several other official side events and sessions, which discussed knowledge sharing, capacity building, networking and explored actionable options for meeting the climate challenge. We attended few country-specific sessions in the African, Japanese, North Korean and EU pavilions on climate education, air pollution, promoting adaptation practices etc. Apart from these events there were several NGOs that raised public awareness and communicated with the delegates. More clarity was required on how countries will share the burden of reducing global greenhouse gas emissions. Many decision making opportunities were postponed for discussions until 2017 and 2018.

It was remarkable to experience this event and witness how the global community comes together to take effective measures to address climate change and combat global warming.

From the Field

Environmental Health Outreach using Traditional Art

In its first outreach initiative, “Our Environment Our Health,” the Centre for Environmental Health partnered with the NGO Happy Hands Foundation to raise awareness of environmental health issues among school children in the National Capital Region, India. The initiative was supported by the Welcome Trust-DBT India Alliance and was part of their Voices for Health series.

Photos: Happy Hands Foundation

Centre researchers and NGO Happy Hands staff worked with women puppeteers to bring puppet shows about sanitation and hygiene and waste disposal to approximately 2800 students (grades 6th and 7th) at 15 public and private schools. The women puppeteers wove the stories around their “lived experience” of cleanliness and sanitation issues in the urban slum of Shadipur, Delhi.

Photos: Happy Hands Foundation

To gauge student understanding and uptake of the information shared through the puppet shows, the students were asked to share their own ideas about pollution and health using another form of traditional storytelling – Patua Art form of West Bengal. With guidance from their teachers, students created “story boards” on topics of their choice, which included hand washing, recycling, and air pollution.

Photos: Centre for Environmental Health

Surveys conducted during the events revealed that more than half of the participating students had previously not known the importance of recycling and sorting garbage; private school children did not wash hands after meals and mostly resorted to dusting their hands off on their uniforms; while in government schools most students did not flush after using the toilet. Some students also enquired about proper hand washing techniques as they were still using ash in their homes. The four month (September – December 2016) effort culminated with a public event in December at a popular city mall where the puppeteers were joined by street theater artists and health experts to raise awareness of air pollution. Students who had participated in the art projects were felicitated at this event. The program was very well received by the public.

This form of participatory engagement using traditional art forms offers an unique and interesting modality to raise awareness of key environmental health issues among school children. Given the positive response from teachers and children, the Centre hopes to use this method in its future outreach campaigns.

Events Calendar

- First Annual Environmental Health Workshop June 5th, 2017, New Delhi

- North East Healthcare Summit September 9-10, 2017, Gangtok, Sikkim

- 17th International Conference of the Public Health Foundation of India and the Pacific Basin Consortium – “Environmental Health and Sustainable Development”

14th-16th November, 2017 - For more information, visit https://pacificbasin.org/.